Last weekend Nesta held their second FutureFest event at Vinopolis, in London. Here are some of the main ideas we picked up from the festival.

Our expectations of robots go beyond their programming.

‘Where are the robots?’ was probably one of the leitmotifs overheard at FutureFest. A mix of curiosity, excitement and fear floated about. What do they look like? What can they do? Are they better at it than us? Are our jobs in danger? Long story short, you apparently have nothing to worry about if you’re a choreographer or funeral attendant, but the rest of us should keep an eye out.

Jobs by probability of automation in 10yrs.

Gutted my funeral won't be attended & led by algorithms :'( #futurefest pic.twitter.com/sYFScAtBZg

— Lydia Nicholas (@LydNicholas) March 14, 2015More interesting questions were provoked by some of the installations present at the festival. For example, The Blind Robot humbled expectations by not being able to do anything but create an opportunity for a non-verbal human-machine interaction. The robot explored the visitor’s face in a manner that recalled the way blind people touch faces in order to familiarise themselves with persons. The questions that inevitably followed each of these rather intimate acts were: ‘Can it see my face?’, ‘Does it know what I look like?’. It could do no such things. But these limitations raised a mirror to our heightened expectations about robots and a hidden desire to be seen and understood by them. A similar experiment was ‘My Robot Companion: Familiar’ - a robot able to take on the appearance of any face it sees. This reiterated this vision of robots as entities being able to see us and ultimately reveal ourselves back to us.

“@petite_a: Interacting with #blindrobot @nesta_uk #FutureFest intriguing mix of joy + slight unease pic.twitter.com/tEjN8P11u8” @bodydataspace

— Ghislaine Boddington (@GBoddington) March 16, 2015Now that we’ve got a better idea of how the mind works, how can we hack it?

Advancements in neuroscience have taken an interesting twist at FutureFest. One of the pervasive ideas was that of tricking the senses to compensate for distance, scarcity or simply convenience. For example, gadgets such as Kissenger - a device for transmitting kisses over the internet, aim to bypass the challenges of distance by simulating touch. Scentee - a fragrance-emitting smartphone add-on, was pitched as a way of tricking your mind into thinking it’s eating, for example, steak when you’re actually on a diet and munching on salad or living on rice as a student. (Not sure how long that trick’s going to last…)

'Scentee' paves the way to sharing all our senses online starting with the smell! #FutureFest @adriancheok pic.twitter.com/GE9H2vd5uz

— Alex Butenko (@butenkoalex) March 15, 2015This idea was also present in Emporious - a vision of the Sweetshop of the Future. Here, in a future where cocoa demand outruns supply, a way of compensating for this scarcity is to shape small quantities of chocolate into spacious architectural forms. These shapes would visually make them seem larger, but also allow for a satisfying tasting experience as they would automatically fill your whole mouth with chocolate.

Space is a luxury. Cocoa is fast becoming a luxury. Chocolate of the future explores space in your mouth #FutureFest pic.twitter.com/4bLgL95SkF

— Jo Lowndes (@lowndesjo) March 15, 2015We’re thirsty for new experiences or, at least, for the ability to enjoy the experiences we’re living.

Perhaps as a response to these increasingly simulated experiences, a number of talks and interactions explored the need to feel - to feel something new, something more powerful, or to simply feel. The NEUROSIS ride gave an example of how neuroscience can be used to create more exciting thrills and push us out of our comfort zones; BitterSuite and Tanya Auclair showed how experiences such as listening to classical music can make us feel more intensely via multiple sensory stimulation using sound, taste, and smell. Even the way we experience food is changing. In reaction to everything being digital and perceived through smooth glass, textures are becoming a trending feature. About time, says Dr. Morgaine Gaye, given that the last major textural innovation in confectionery was Pop Rocks in the 70s.

That said, some pretty awesome examples of cool new foods experiences here #FutureFest # pic.twitter.com/EHbLmoYoKK

— Noah Raford (@nraford) March 15, 2015In parallel to this tendency to crank up the intensity of our experiences in order to feel more, Paul Dolan posed a nice complementary challenge. He argued for an approach towards silencing some of these potential distractions and nurturing an internal ability to listen to what we are feeling in the present.

Decentralise everything - from financial systems and politics, to music making.

Whether the talk was about the future of finance, the internet, or politics, the need for decentralisation as a way of involving the wider community and reinstating trust in the system was prevalent. Debates often revolved around the role technology could play in this process. A particularly insightful example of this came from the music industry. Spoek Mathambo, a South African artist, spoke about the decentralisation of music making while introducing his documentary, Future Sounds of Mzansi.

Awesome stuff from @SPOEK_MATHAMBO at #futurefest access to technology + democratisation of Internet = new music pic.twitter.com/3evpCZV0Ul

— Philip Colligan (@philipcolligan) March 15, 2015He identified genres of electronic music that developed at the same time that pirated copies of music-making software like Fruityloops was passed around on CDs in South African townships. He also spoke of the importance of online audio distribution platforms like Soundcloud and a South African site called Kasimp3 whose success in spawning new sub-genres is partly due to the fact that it works so well on non-smart phones.

Coding is the language of the 21st century. How to get more people to speak it and be part of the conversation?

Technology is embedded in our day to day lives from the ways in which we communicate with each other, we make transactions, or even express political opinions. Yet as these technologies become increasingly sophisticated, the ability of digitally illiterate individuals to participate and have a say in their creation is limited. Either directly or indirectly, debates bought up the need for an educated - or at least informed - user who can have a say in the development of these technologies and an understanding of their impact.

. @VitalikButerin "C++ and Python are the new Latin and Greek." Cryptography is becoming the people's militia. #FutureFest

— Science Practice (@sciencepractice) March 15, 2015Coding classes re-emerged as an approach towards encouraging a broader engagement and dialogue from a young age, while other debates focused on encouraging a greater diversity in gender and race among tech creators.

More gender & race diversity in tech creators would mean far more interesting tech - @helenlewis at #FutureFest pic.twitter.com/EFSLVQOwnm”

— Dani Mansfield (@DaniMansfield) March 15, 2015Finally, on a topic closer to home…

How to visualise abstract ideas and avoid ‘dummifying’ data.

The ‘Information is Dutiful’ debate opened up an interesting space for talking about the purpose of data visualisations and the challenges they pose. Panellists included: Francine Bennett (CEO at Mastodon C), Hannah Radler (associate curator at Open Data Institute) and Matthew Falla (partner at Signal | Noise). After the initial presentation of portfolios, the audience asked questions about the standards of sharing and use of patient data in a clinical context. Although a 45-minute debate is not a place where problems of this magnitude can be solved, it was encouraging to see there is already a strong awareness of existing issues around the use of patient data. Another point raised by the audience addressed the risk of ‘dummifying’ data when it is visualised. Although at Science Practice we like to think that it is in fact one of the key responsibilities of a designer to curate all relevant information in the visualisation (similarly to transformers’ duties at ISOTYPE), we can relate to these concerns. Many visualisations (aka ‘infographics’) are designed with too much emphasis on their visual beauty, compromising the veracity of data.

Data visualization - know what you're missing. #futurefest cartoon pic.twitter.com/5HXSkPtCf8

— Virpi Oinonen (@voinonen) March 15, 2015Another relevant question related to the use of proxies in data visualisations of abstract ideas. When one wants to visualise, for example, data about innovation, one has to find a quantifiable proxy for the abstract concept of innovation in general. Data on the use of Github might seem a good proxy here, but it also means leaving out all innovation that is not software development. Is this a fair approximation? We’re not sure. Although the panellists gave no absolute answers to the proxies question, the real value is in the question itself and in recalling it again each time we’re working on another visualisation piece.

Thank you for the food for thought FutureFest and looking forward to helping shape some of these futures to come!

Yesterday, Apple held one of its Keynote events. Amongst talk of super-thin minimalist laptops and $10,000 luxury smart watches, we were also very excited by the announcement of ResearchKit. This interests us both as Science Practice and as part of SP+EE where we work on healthcare-related projects, including design and development of software for medical research.

We spent some time today delving a bit deeper into ResearchKit, so here are a some initial notes along with a few open questions that we hope will be answered soon:

- ResearchKit is a software framework that allows researchers to run medical studies using the participant’s own iPhones as the primary means of gathering data. The idea is that ResearchKit should make it easy for medical researchers to collect more data from larger and more varied study groups, more frequently. This point was quite nicely illustrated in a tweet by John Wilbanks:

After six hours we have 7406 people enrolled in our Parkinson's study. Largest one ever before was 1700 people. #ResearchKit

— John Wilbanks (@wilbanks) March 10, 2015-

Importantly, the code will be open source meaning that, when it is released, anyone will be able to download and start building on top of the platform. Hopefully this will encourage a community of developers and researchers to form and share useful modules. These might not be limited to software alone, but also reusable design patterns, ethically approved content and best-practices.

-

ResearchKit has a technical overview document which can be found here. This document contains information about the main modules ResearchKit will have. These are designed to reflect the most common elements within a clinical study: a survey module, an informed consent module and an ‘active tasks’ module.

-

Interestingly, the technical overview documentation also has a list of things that ResearchKit doesn’t include, such as the ability to schedule tasks for participants. We’ve found scheduling tasks and reminders to be a more-or-less essential feature in similar types of study we’ve been involved in, so this is probably on Apple’s todo list.

-

Apple also states that it doesn’t include automatic compliance with research regulations and HIPAA guidelines. This places the responsibility firmly on the researchers. However, as the developer and research community around ResearchKit establishes itself, perhaps best-practices will be developed and shared to help streamline compliance in a range of international regulatory contexts.

-

In an interview in Nature, Stephen Friend, president of Sage Bionetworks states that “At any time, participants can also choose to stop. The data that they have contributed stays in, because you don’t know who they are”. This standpoint doesn’t quite chime with us. Perhaps other consent models will be possible where a participant can optionally remove their data from a study if they decide to leave. It’s their data after all.

-

In the same article, Ray Dorsey from University of Rochester in New York comments on the the most obvious problem with ResearchKit: sampling bias. He points out that “the study is only open to individuals who have an iPhone, specifically the more current editions of the iPhone”. We can imagine a port of ResearchKit to Android popping up fairly quickly once the source code is released, but bias will always be an important consideration in studies that require participants to have smartphones, regardless of the manufacturer.

-

It will also be interesting to see how the peer reviewers will interpret the quality of the data collected by the ResearchKit enabled apps when the results begin to be published.

It looks like a fascinating platform and we will be watching eagerly as it develops and maybe even jumping on-board too.

After our call for a Challenge Prizes intern a week ago, we have had a number of fantastic applicants. Thank you to everyone who got in touch!

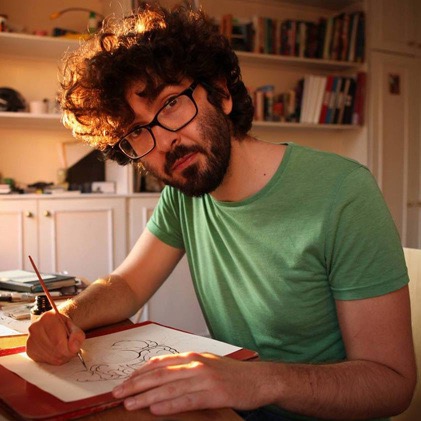

One of the more unexpected enquiries we received came from Matteo Farinella. Matteo has a PhD in Neuroscience from UCL and has since been working as an illustrator creating info-comics and scientific illustrations. We have been following Matteo from afar over the last few years: admiring work like Neurocomic and noting his recent success in the Vizzies, so it was great to hear from him.

Matteo will be joining us for a few months to support us on an exciting new Challenge Prizes project. One slight problem: Matteo is grossly overqualified to be an intern. So, while Matteo will be helping with the research we originally needed an intern for, he’ll be doing a whole lot more too.

Update 05/03/2015: Call now closed. Thank you to those who applied!

#We’re looking for a research intern with a passion for technology and innovation to join our team.

- Salary: Paid Internship

- Location: 83-85 Paul Street, London EC2A 4NQ, UK

- Term: 3 months

- Hours: Full-time

- Starting date: Immediately

In case you haven’t met us yet - we’re Science Practice, a design and research company based in London. We work across a variety of areas but central to our mission is creating an explicit role for design in scientific practice. Whether we’re designing challenge prizes, prototyping microfluidic chips or creating new methods for visualising genetic data, we’re always looking at ways to integrate design principles with the processes and methodologies of science.

We are a multidisciplinary team of five with very diverse backgrounds and skills ranging from design and business, to biomedical engineering, but with a unifying passion and curiosity for scientific innovation.

We are looking to recruit a recent university graduate to support a project to create several challenge prizes. This is a really exciting area that involves futures research into new technologies and disruptive innovations able to provide a solution to some of today’s most pressing problems. The challenge prizes will focus on different areas such as robotics, biometric security, quantum computing and digital currencies. We are looking for someone knowledgeable, inquisitive and passionate about new and emerging technologies and the potential they hold.

#The role will involve:

- Researching technological innovations and their impact on addressing social problems;

- Writing key research findings and helping prepare external project documentation;

- Supporting expert engagement work - this includes identifying key experts in a specific field, arranging and taking part in interviews, and synthesising main ideas;

- Working closely with a team of international partners in designing the structure of several challenge prizes;

- Completing important and often time sensitive ad hoc project tasks.

#The person we’re looking for:

- Passionate about technology and its potential for social impact;

- Interested in innovation and tools for supporting innovation such as challenge prizes or competitions;

- Strong academic credentials - recent graduate of a Bachelors or Masters (preferably in a technology related degree), with a 2.1 or higher;

- Strong research skills - ability to understand and synthesize complex information quickly;

- Strong communication and writing skills;

- Organised, with a close attention to detail;

- Work efficiently, be flexible and manage priorities to meet deadlines;

- Self-motivated and inquisitive - an ability to work autonomously but seek advice when needed;

- Able to work on location in London, UK;

- (And if you really want to tick all the boxes): design/programming skills.

If you’re interested in applying for this role, please send an email with your CV to Ana at af@science-practice.com. Thanks and looking forward to hearing from you soon!

In February 2014 we started work on the Longitude Prize. How we approached this project and what we learned along the way is the topic of the following posts:

After almost four months of interviews with over 100 experts and multiple design iterations we had accumulated a lot of valuable knowledge; the next step was to synthesise and validate this knowledge with a wider expert audience. We began writing up the six challenge prize design proposals into ‘challenge reports’.

Writing these initial reports wasn’t an easy task. We wanted them to offer readers a guided explanation of the decisions made during the research and design process. We wanted to show where there was a clear consensus, but also highlight areas that were still in need of further discussion.

To do this we structured the reports to reflect our research process. Reports began by describing the broad problem area, then gradually started focusing in on the challenge area, the role the challenge prize would play in addressing the core problem, and the types of solutions encouraged. This gradual ‘zooming in’ allowed us to present our arguments and the decision-making process behind the proposed design. It also meant that a contentious element or argument could be traced back to an initial decision point that could then be discussed.

Diagram showing the decision points for the Antibiotics prize with our recommended option at each stage

Challenge Reports in Practice

Once written, we validated these reports with experts. This time around, we wanted experts to act as reviewers. We wanted them to understand that the document we were presenting to them was close to a final challenge prize design, but we still wanted them to actively contribute to its structure. For this purpose, we scattered questions throughout the reports and added an Appendix with key issues other experts brought up in previous conversations.

Although we are aware that there is nothing particularly original about this process, it was very valuable for us as it drew attention to misunderstandings and oversights on our part.

After several iterations each challenge area had an accompanying report that narrated the journey of designing its challenge prize and the decisions made along the way. All we needed to know now was which one of these challenges was going to become the Longitude Prize 2014.

All six Longitude challenge reports

And the Winner is…

Dr Alice Roberts announcing the result

On 25 June 2014 Antibiotics was announced as the winner of the British public’s vote to become the topic of the Longitude Prize. Following this announcement, a decision was made to share the Antibiotics challenge report with the general public to get a broader input on the proposed prize structure.

To make the report more accessible we included some additional features. We added illustrations for some example diagnostic tools to make the types of solutions sought more concrete. We included additional visualisations to support the parameters and, most importantly, we added a diagram of the prize assessment process to help competitors understand what is expected from them at the different prize phases.

Diagram explaining the Longitude Prize assessment process

Following these changes, the Antibiotics challenge report was published on the Nesta website with the aim to engage the general public in discussions around the Longitude Prize and get their feedback on the structure of the Antibiotics challenge. Based on this report and the feedback from the open review the final Longitude Prize 2014 Prize Rules were created.

Wrapping up the Longitude Project

The experience of researching and designing the six candidate challenges for the Longitude Prize was a very valuable one for us. It gave us the opportunity to explore new ways of engaging with experts and learn how to make best use of their expertise.

In our write up of this project we have placed an emphasis on the design proposals we used to prompt discussions. We did this to highlight their role in supporting more focused, specific and constructive discussions. At a more fundamental level, this process meant that the researcher took responsibility for the creative quality of the ideas being discussed - something that can often lack in research that seeks to canvas the opinion of many stakeholders.

Now that our work on the project is done, we’re eagerly looking forward to seeing the innovations the Longitude Prize 2014 will bring!

You can read the full Antibiotics challenge report here and the Prize Rules here.

Think you’ve got an idea about how to solve the Longitude Prize 2014? Register your team here. Good luck!